Studies (scroll for more studies and click to enlarge individual images)

In December 2011 I wanted to make two small paintings for a scholarship fundraiser. I cannibalized a chunk of wood from an old work I had been saving for such an occasion and marked off 5x7 inch areas. On these I quickly painted details from two of my favorite Sanford Gifford paintings. I had so much fun that I made a third, and then a fourth, and now there are 13 small works (c. 10x13 inches) which reference a spread of my favorite Hudson River School icons. During the course of this miniature explosion I have revisited notions regarding the actual interpretation of what those Hudson River School artists were showing us. Those art historical interpretations have haunted me over the past nine years. I am placing my miniature studies with a text on this site, not only to share my mental and physical journey with friends, but to try, at the same time, to see how my thinking has developed or changed over this period of time. I have outlined my various trips to classic Hudson River School terrain. Discoveries are listed in order. I had thought of writing my observations on the reverse of each small painting, but for the moment it actually made more sense to list these thoughts and observations on a blog. (This blog will be the “what’s happening in the studio” arm of my kendixonart.com website.)

To offer more perspective I should say that I generally choose a reference to Hudson River School painting to serve as my metaphor for “Order” in my Order & Disorder series. Schooled to the notion that these works were essentially metaphysical and transcendental in nature, over the past nine years I have changed my mind about that single interpretation. I knew Hudson River School artists sketched and made painted studies on site and their work began as a record of what they saw. Accidental discoveries made while traveling in Vermont and Massachusetts in 2003 coupled with ensuing revelations from travel and reading have brought me to these observations: artists did point out (intentionally or unintentionally) the degradation of a landscape by intense deforestation; air pollution and rapid erosion of the landscape were a by-product of this deforestation; expansive vistas were made possible by the massive clear-cutting of trees; veiled or colorful sunsets and sunrises were often caused by pervasive smoke pollution. I would note too, that even some painting titles might be seen as metaphors that reference the spiritual and physical destruction brought about by the civil war as well as massive environmental destruction created by an overzealous population.

Geographic note: at the height of Hudson River School production, artists were depicting a natural world that had been dramatically changed from what it was at the beginning of the l9th century. The old ice age forests of spruce, white pine, cedar, and hardwood in the NE United States had been mined by commercial interests and turned into fuel, houses, sailing ships, commercial wagons, barges, potash (used in gunpowder, soap, and fertilizer) and charcoal. The courses of rivers and creeks had been altered as well.

I have found no artist other than Thomas Cole who wrote or spoke openly about what they saw. Perhaps when progress is moving rapidly, the artist only has time to record what they observe. However, it is also clear from my reading that the patrons who bought and commissioned many of these artworks were often the heads of industries at the leading edge of resource exploitation.

To offer more perspective I should say that I generally choose a reference to Hudson River School painting to serve as my metaphor for “Order” in my Order & Disorder series. Schooled to the notion that these works were essentially metaphysical and transcendental in nature, over the past nine years I have changed my mind about that single interpretation. I knew Hudson River School artists sketched and made painted studies on site and their work began as a record of what they saw. Accidental discoveries made while traveling in Vermont and Massachusetts in 2003 coupled with ensuing revelations from travel and reading have brought me to these observations: artists did point out (intentionally or unintentionally) the degradation of a landscape by intense deforestation; air pollution and rapid erosion of the landscape were a by-product of this deforestation; expansive vistas were made possible by the massive clear-cutting of trees; veiled or colorful sunsets and sunrises were often caused by pervasive smoke pollution. I would note too, that even some painting titles might be seen as metaphors that reference the spiritual and physical destruction brought about by the civil war as well as massive environmental destruction created by an overzealous population.

Geographic note: at the height of Hudson River School production, artists were depicting a natural world that had been dramatically changed from what it was at the beginning of the l9th century. The old ice age forests of spruce, white pine, cedar, and hardwood in the NE United States had been mined by commercial interests and turned into fuel, houses, sailing ships, commercial wagons, barges, potash (used in gunpowder, soap, and fertilizer) and charcoal. The courses of rivers and creeks had been altered as well.

I have found no artist other than Thomas Cole who wrote or spoke openly about what they saw. Perhaps when progress is moving rapidly, the artist only has time to record what they observe. However, it is also clear from my reading that the patrons who bought and commissioned many of these artworks were often the heads of industries at the leading edge of resource exploitation.

A Journey of Connecting Dots

August 2003 Middlebury, VT

There is a war memorial that lists the names of Middlebury individuals who gave their lives in service. The list of the Civil War dead greatly outnumbers the individual lists for World War I and World War II.

(3 days later) Vermont State House, Montpelier

While standing in front of enormous paintings which honor the Vermont regiments in service during the Civil war our docent commented that VT liked to claim it was one of the major players and a deciding force in the Union victory.

(same day) Home of Senator Justin Morrill, Stafford, VT

When you drive most two lane highways in VT you feel like you are in a Currier & Ives print. The southern mountains (many old terminal moraines from the last ice age) are completely forested with hardwoods (occasional evergreen stands). The thick forests on the hills of the Morrill farm look like they might have been there for the early Native Americans. On the tour to the second story of the home you encounter a window which looks out on these hills. On a wall adjacent to this real-time view is a B&W 19th century photograph of these same hills. Those in the photo were as barren as anything you might see in the SW United States. There was no text to explain the contradiction.

(days later) Vermont Public Television, Middlebury

An accidental encounter during dinner with the motel room TV presented an interview with VT author Jan Albers. Albers had published a research volume (MIT Press 2000) titled Hands on the Land --- the Vermont Landscape. The premise of her research is basically that all landscape is political --- that landscape is a living record of our interaction with it --- an interaction which reflects our values and our decisions. The ensuing Q & A of this interview pulled all my observations of the previous days together. Simply put, by 1860 the citizens and industries of VT had taken a highly forested post- glacial evergreen and fresh-water landscape and turned it into a mess. There was no timber left to cut, there were no logs to feed the lumber mills, and no lumber for construction. Bare hills and flood plains had eroded, compromising agriculture and local fishing industries. By 1860 there were no jobs for young men. They were left with two choices, become employed by the Union army or join the migration West. (Vermont sent 34,000 men to the war from a state population of 340,000.)

As Vermont observations coalesced, my thought shifted to question the possibility of parallel events which might have occurred in other NE regions earlier, or simultaneous to Vermont’s environmental story. How much did the 19th century view of its timber and landscape wealth contribute to the vistas at which these Hudson river artists were looking and showing us in their work? I wondered how many “transcendental visions” of light, space, and color in 19th century landscape painting had been made possible by clear cutting or the felling of trees which stood in the way of a better view or stood in the way of progress.

October 2003 (Oxbow; Catskills; Frederick Church Home; Hudson Valley)

There is a mountain called Holyoke directly across the Connecticut River from Northampton, MA. When you reach the summit (by car) you find the site of historic tourist accommodations (earliest built in 1821, current Prospect House 1851). From the face of these accommodations is the sweeping view of the Connecticut River and the oxbow recorded in Thomas Cole’s painting View From Mt. Holyoke After a Thunderstorm --- The Oxbow 1836. The only problem being that there is no longer an oxbow attached to the river. The river became a straight line in 1840 when the pressure of flood waters broke the neck of the oxbow. I believe Cole saw this inevitable destruction because of the lack of protection afforded the land due to the cutting of trees and encroachment of farmland. Now, the shape of the oxbow is barely visible from Holyoke as trees largely mask a marina which has been installed, along with the roadbed of I-91 on the western edge of the old oxbow. On its eastern side the roadbed of route 5 crosses what was the old neck of the oxbow. Distant hills and other geographic undulations, visible in Cole’s painting are now covered and disguised by the “urban maples” of East Hampton and Northampton. There is still farmland near the river, but there is no evidence of the massive clearing shown in Cole’s painting where even the river banks are nude to our view.

The dramatic differences on this site only made me wonder about the information artists were referencing from those other sites which they made famous. I understand now that I was given a clue when I visited the home of Frederick Church (Olana in Catskill, NY) several days later. Church, who I see as the more ardently romantic and transcendental of my favorites, after 1860 focused less on American landscape and more on the landscape of undeveloped and less-developed sites south of the American border.

March 2004 Amon Carter Museum, Ft. Worth, TX

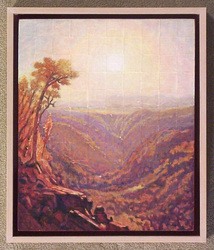

Sanford Gifford (1823-1880) Retrospective

I lucked into the opening reception for this exhibition. The catalogue (published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art 2003) was a revelation. Its narrative not only attempted to solve a discussion about landscape sites which influenced Gifford’s work, but the catalogue included place-names, maps and directions to some of these sites. Armed with this information I planned a Spring visit back to MA and NY at a time when there was less foliage on the trees.

May 2005 Catskill Mountains Haines Falls, NY (MA, CT, NH, NY)

Catskill Forest Preserve: North & South Lake; Catskill Mountain House; Laurel Mountain House; Katterskill Falls and Katterskill Gorge

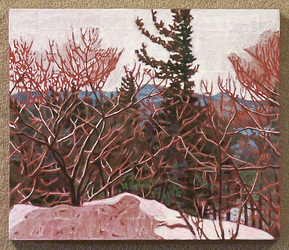

The importance of these sites is that they were used heavily by 4 of my favorites --- Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Jasper Cropsey, and Sanford Gifford. Tourist hotels were built in the late 1820’s near Katterskill Falls and on a Hudson Valley overlook near North and South Lakes. Over a 20 year period at North & South Lake and Katterskill Falls those four artists pretty much reference the same sites (1844-1862). Often it is from the same vantage point on the trails. My supposition is that these cleared areas were initially developed for the convenience of guests visiting the Catskill House or the Laurel House. Mountain rock in the NE (largely granite) is tough and does not decompose rapidly. The trails of the early 19th century are still in use today and an old good lookout spot is still a lookout spot. In most cases, now, trees are in the way of the historic painted view. As I hiked on those trails and looked at the composition and location of the current flora, I understood why I had so much trouble trying to paint renditions of Durand, Cole, Cropsey and Gifford for my Order/Disorder series. I assumed I was looking at mature forests in the paintings which I referenced. I understand, now, that when they painted the landscape, they were not only working with clear-cuts which opened their view, but they were generally painting floral cover that was “new growth” hardwood trees (a maple sapling forest) that had come in to replace the old evergreen cover which had been “mined”.

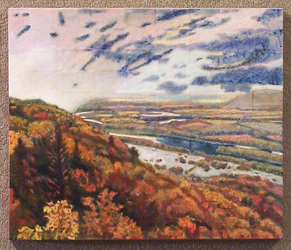

Note on geography: The glacial era in the NE ends c. 10,000 leaving Canada and the North covered with moraines, glacial-melt lakes (often in strange locations like on TOP of a mountain) and a cover of evergreen forests. Hardwood trees (red maple, walnut, oak, etc) principally grew in the understory or in the forest meadows. Hardwoods grow more quickly and are more tolerant than the large evergreens. So when the evergreen forest was taken off in the NE it was quickly replaced by red maple and other hardwoods. (Jan Albers says that this was the birth of what we now call the traditional NE autumn phenomenon---intense Fall color.) I thought her observation added another ingredient into my attempt at understanding American landscape painting in the NE. This Hudson River love of the autumnal landscape is pervasive and could be noted as something completely new to the artistic and cultural experience of the 1840’s.

July 2005 Houston, TX

While house-sitting, a “field-trip” to a local used book store yielded an accidental and important find --- a catalogue from the exhibition American Sublime - Landscape Painting in the United States 1820-1880 (Tate Museum, London 2002). One essay by Tim Barringer (Professor of Art History, Yale) included ideas about 19th century Hudson River School production and probable influences both from political movements as well as concerns by some members of that artistic community regarding past and current degradation of the environment. This essay gave me the boost I needed to continue pursing this line of thinking.

August 2003 Middlebury, VT

There is a war memorial that lists the names of Middlebury individuals who gave their lives in service. The list of the Civil War dead greatly outnumbers the individual lists for World War I and World War II.

(3 days later) Vermont State House, Montpelier

While standing in front of enormous paintings which honor the Vermont regiments in service during the Civil war our docent commented that VT liked to claim it was one of the major players and a deciding force in the Union victory.

(same day) Home of Senator Justin Morrill, Stafford, VT

When you drive most two lane highways in VT you feel like you are in a Currier & Ives print. The southern mountains (many old terminal moraines from the last ice age) are completely forested with hardwoods (occasional evergreen stands). The thick forests on the hills of the Morrill farm look like they might have been there for the early Native Americans. On the tour to the second story of the home you encounter a window which looks out on these hills. On a wall adjacent to this real-time view is a B&W 19th century photograph of these same hills. Those in the photo were as barren as anything you might see in the SW United States. There was no text to explain the contradiction.

(days later) Vermont Public Television, Middlebury

An accidental encounter during dinner with the motel room TV presented an interview with VT author Jan Albers. Albers had published a research volume (MIT Press 2000) titled Hands on the Land --- the Vermont Landscape. The premise of her research is basically that all landscape is political --- that landscape is a living record of our interaction with it --- an interaction which reflects our values and our decisions. The ensuing Q & A of this interview pulled all my observations of the previous days together. Simply put, by 1860 the citizens and industries of VT had taken a highly forested post- glacial evergreen and fresh-water landscape and turned it into a mess. There was no timber left to cut, there were no logs to feed the lumber mills, and no lumber for construction. Bare hills and flood plains had eroded, compromising agriculture and local fishing industries. By 1860 there were no jobs for young men. They were left with two choices, become employed by the Union army or join the migration West. (Vermont sent 34,000 men to the war from a state population of 340,000.)

As Vermont observations coalesced, my thought shifted to question the possibility of parallel events which might have occurred in other NE regions earlier, or simultaneous to Vermont’s environmental story. How much did the 19th century view of its timber and landscape wealth contribute to the vistas at which these Hudson river artists were looking and showing us in their work? I wondered how many “transcendental visions” of light, space, and color in 19th century landscape painting had been made possible by clear cutting or the felling of trees which stood in the way of a better view or stood in the way of progress.

October 2003 (Oxbow; Catskills; Frederick Church Home; Hudson Valley)

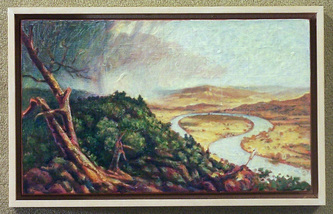

There is a mountain called Holyoke directly across the Connecticut River from Northampton, MA. When you reach the summit (by car) you find the site of historic tourist accommodations (earliest built in 1821, current Prospect House 1851). From the face of these accommodations is the sweeping view of the Connecticut River and the oxbow recorded in Thomas Cole’s painting View From Mt. Holyoke After a Thunderstorm --- The Oxbow 1836. The only problem being that there is no longer an oxbow attached to the river. The river became a straight line in 1840 when the pressure of flood waters broke the neck of the oxbow. I believe Cole saw this inevitable destruction because of the lack of protection afforded the land due to the cutting of trees and encroachment of farmland. Now, the shape of the oxbow is barely visible from Holyoke as trees largely mask a marina which has been installed, along with the roadbed of I-91 on the western edge of the old oxbow. On its eastern side the roadbed of route 5 crosses what was the old neck of the oxbow. Distant hills and other geographic undulations, visible in Cole’s painting are now covered and disguised by the “urban maples” of East Hampton and Northampton. There is still farmland near the river, but there is no evidence of the massive clearing shown in Cole’s painting where even the river banks are nude to our view.

The dramatic differences on this site only made me wonder about the information artists were referencing from those other sites which they made famous. I understand now that I was given a clue when I visited the home of Frederick Church (Olana in Catskill, NY) several days later. Church, who I see as the more ardently romantic and transcendental of my favorites, after 1860 focused less on American landscape and more on the landscape of undeveloped and less-developed sites south of the American border.

March 2004 Amon Carter Museum, Ft. Worth, TX

Sanford Gifford (1823-1880) Retrospective

I lucked into the opening reception for this exhibition. The catalogue (published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art 2003) was a revelation. Its narrative not only attempted to solve a discussion about landscape sites which influenced Gifford’s work, but the catalogue included place-names, maps and directions to some of these sites. Armed with this information I planned a Spring visit back to MA and NY at a time when there was less foliage on the trees.

May 2005 Catskill Mountains Haines Falls, NY (MA, CT, NH, NY)

Catskill Forest Preserve: North & South Lake; Catskill Mountain House; Laurel Mountain House; Katterskill Falls and Katterskill Gorge

The importance of these sites is that they were used heavily by 4 of my favorites --- Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Jasper Cropsey, and Sanford Gifford. Tourist hotels were built in the late 1820’s near Katterskill Falls and on a Hudson Valley overlook near North and South Lakes. Over a 20 year period at North & South Lake and Katterskill Falls those four artists pretty much reference the same sites (1844-1862). Often it is from the same vantage point on the trails. My supposition is that these cleared areas were initially developed for the convenience of guests visiting the Catskill House or the Laurel House. Mountain rock in the NE (largely granite) is tough and does not decompose rapidly. The trails of the early 19th century are still in use today and an old good lookout spot is still a lookout spot. In most cases, now, trees are in the way of the historic painted view. As I hiked on those trails and looked at the composition and location of the current flora, I understood why I had so much trouble trying to paint renditions of Durand, Cole, Cropsey and Gifford for my Order/Disorder series. I assumed I was looking at mature forests in the paintings which I referenced. I understand, now, that when they painted the landscape, they were not only working with clear-cuts which opened their view, but they were generally painting floral cover that was “new growth” hardwood trees (a maple sapling forest) that had come in to replace the old evergreen cover which had been “mined”.

Note on geography: The glacial era in the NE ends c. 10,000 leaving Canada and the North covered with moraines, glacial-melt lakes (often in strange locations like on TOP of a mountain) and a cover of evergreen forests. Hardwood trees (red maple, walnut, oak, etc) principally grew in the understory or in the forest meadows. Hardwoods grow more quickly and are more tolerant than the large evergreens. So when the evergreen forest was taken off in the NE it was quickly replaced by red maple and other hardwoods. (Jan Albers says that this was the birth of what we now call the traditional NE autumn phenomenon---intense Fall color.) I thought her observation added another ingredient into my attempt at understanding American landscape painting in the NE. This Hudson River love of the autumnal landscape is pervasive and could be noted as something completely new to the artistic and cultural experience of the 1840’s.

July 2005 Houston, TX

While house-sitting, a “field-trip” to a local used book store yielded an accidental and important find --- a catalogue from the exhibition American Sublime - Landscape Painting in the United States 1820-1880 (Tate Museum, London 2002). One essay by Tim Barringer (Professor of Art History, Yale) included ideas about 19th century Hudson River School production and probable influences both from political movements as well as concerns by some members of that artistic community regarding past and current degradation of the environment. This essay gave me the boost I needed to continue pursing this line of thinking.

May 2006; October 2008; October 2010

The pursuit of sites continues, mostly to those used by Sanford Gifford in MA, ME, NH and NY. Another trip to the Catskills is planned for Fall 2012 to explore sites higher on the ridge trails at North & South Lake. I would like to find the view used by Sanford Gifford in his two paintings A Gorge in the Mountains and October in the Kattskills, which show a high, distant view of Katterskill Falls with North & South Lake on the horizon behind Katterskill Falls.

The pursuit of sites continues, mostly to those used by Sanford Gifford in MA, ME, NH and NY. Another trip to the Catskills is planned for Fall 2012 to explore sites higher on the ridge trails at North & South Lake. I would like to find the view used by Sanford Gifford in his two paintings A Gorge in the Mountains and October in the Kattskills, which show a high, distant view of Katterskill Falls with North & South Lake on the horizon behind Katterskill Falls.

Observations Emanating From the The Studies

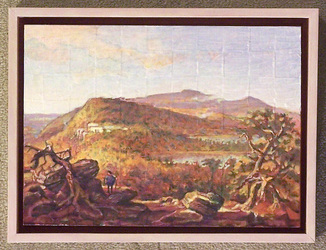

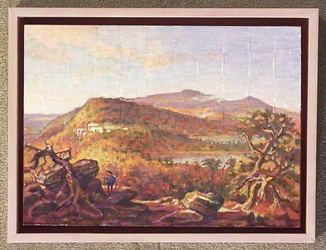

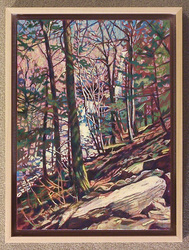

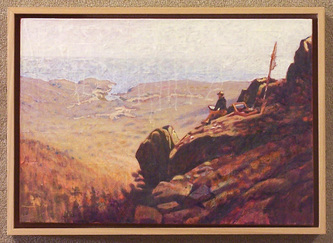

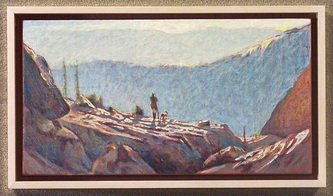

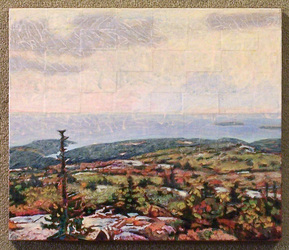

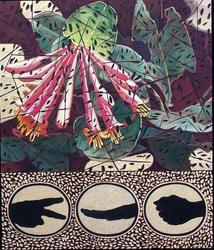

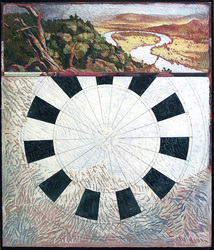

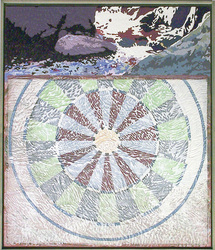

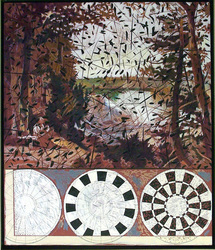

The following works are in acrylic on wood. The surface of each board is first collaged with a woven pattern made from U.S. commemorative postage stamps or is textured with a pattern of woven squares made with layers of paint.

The following works are in acrylic on wood. The surface of each board is first collaged with a woven pattern made from U.S. commemorative postage stamps or is textured with a pattern of woven squares made with layers of paint.

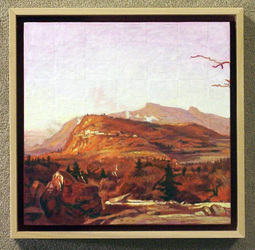

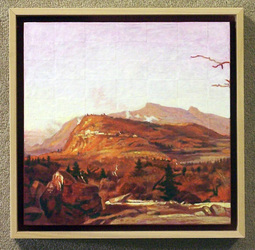

The 3 paintings of the Catskill Mountain House (in full operation by 1825) occur over 18 years: Thomas Cole in 1844; Jasper Cropsey 1855; and Sanford Gifford 1862. Cole’s view is higher in elevation and vertical from the spot Cropsey chooses. Gifford’s view appears to be from the old ridge trail on North Mountain above where Cole and Cropsey worked. When I located the viewpoint used by Jasper Cropsey on my 2003 visit to this location, I found that trees obscured any view of the site of the now destroyed Mountain House. Blue patches locating South & North Lake could be seen through the trees. I could visually follow the unique ridge line of the distant mountains behind South Mountain through the Spring foliage. As I walked around on the mountain trails opposite the old Mountain House site, it became obvious to me that none of the landscapes described in these 3 paintings were as densely forested as my imagination could conjure when I first saw the paintings. Now I look at the paintings and see a lot of new-growth hardwood filling in places that tree removal had cleared.

While working on these studies I started to pay closer attention to the white “mist” that rises to the right back (above the hotel) of South Mountain and also occurs (in the same places and in a larger amounts) in Cropsey’s painting. In Cropsey’s gaze this “mist” gets much darker when it moves up across the sky --- the way smoke would act. Gifford’s gaze at the Mountain House does not turn far enough to the right to reveal this area. However, Gifford’s work from 1880, October in the Kattskills, is a view looking east towards Katterskill Falls with the two lakes and the Hudson Valley on the far horizon. Gifford shows a plume of smoke rising from this same general location that is noted in the Cole and Cropsey paintings. I’m guessing that the low white clouds which rise from the mountain in the Cole and Cropsey Mountain House paintings and in the Gifford painting, October, are more likely smoke from a charcoal or potash production site.

While working on these studies I started to pay closer attention to the white “mist” that rises to the right back (above the hotel) of South Mountain and also occurs (in the same places and in a larger amounts) in Cropsey’s painting. In Cropsey’s gaze this “mist” gets much darker when it moves up across the sky --- the way smoke would act. Gifford’s gaze at the Mountain House does not turn far enough to the right to reveal this area. However, Gifford’s work from 1880, October in the Kattskills, is a view looking east towards Katterskill Falls with the two lakes and the Hudson Valley on the far horizon. Gifford shows a plume of smoke rising from this same general location that is noted in the Cole and Cropsey paintings. I’m guessing that the low white clouds which rise from the mountain in the Cole and Cropsey Mountain House paintings and in the Gifford painting, October, are more likely smoke from a charcoal or potash production site.

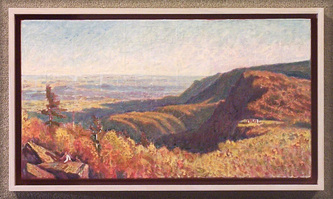

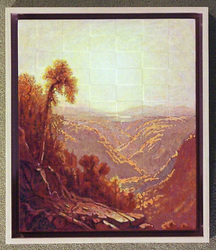

From 1862 to 1880 Sanford Gifford made a number of small (11 x 13 inch) studies from this location as well a two finished canvases. It is a vantage point I want to find this year now that I have figured out where he was sitting . The 1880 work gives the impression of North & South Lake on the ridge behind the white glint of Katterskill Falls which drops off the distant elevation. As I noted above, in the 1880 painting, a smoke plume is obvious on the level to the right of the lakes. When I first saw this painting I imagined that the glow of the morning sun was rising over the Hudson River Valley through a foggy morning mist. Now I can just as easily imagine that I am looking at the sun rising through a smoky haze created by a morning temperature inversion that is not allowing the persistent wood smoke to dissipate.

Ideas concerning Cole’s Thunderstorm on the Connecticut --- Oxbow have already been introduced. Here are other notations I want to add. Google leads to an article about a geology professor from Amherst College who was so aware of the oxbow’s vulnerability that in 1840 when he heard about the volume of flood water building up-river, he was able to transport his students to the top of Mt. Holyoke in time that they might witness the oxbow being detached from the river. (Talk about a class field trip! In case you were wondering, Amherst is on the SAME side of the river as Mt. Holyoke.) I tried for years (in Northampton Public Library, etc) to find the date of this flood. Three years ago I found a general date with no details. This spring, Google offered the above eye-witness account. Another interesting story is in the Tim Barringer essay for the catalogue Images of the Sublime – Landscape Painting in the US (Tate Museum, London 2002). He writes about Thomas Cole’s awareness of the rapid deterioration of the American landscape around him and notes that the Oxbow painting was being started as Cole was finishing his 5 canvas series The Course of Empire. Barringer footnotes Thomas Cole stating that Thunderstorm --- Oxbow was painted on the canvas which he (Cole) had used to sketch his ideas for #5 in the Course of Empire series. Consummation of Empire is #5.

Cole’s vantage point on the oxbow is down river (south) from my study, presumably out on the point of the hill which appears on left edge of my study. I have not been able to get to this spot -- too much vegetation is in the way. How this would have been handled in Cole’s time was that the area would have been cleared for viewing.

Cole’s vantage point on the oxbow is down river (south) from my study, presumably out on the point of the hill which appears on left edge of my study. I have not been able to get to this spot -- too much vegetation is in the way. How this would have been handled in Cole’s time was that the area would have been cleared for viewing.

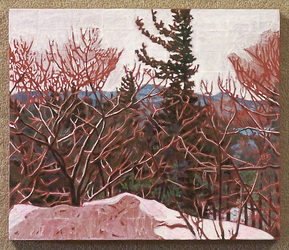

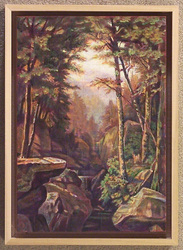

These two studies are from Katterskill Gorge at the bottom of Katterskill Falls. The first study is from a work by George Hetzel, Rocky Gorge 1869. I wanted to work with this painting because it has so many of the foreground landscape elements seen in Asher Durand’s Kindred Sprits. In Durand’s painting Thomas Cole and William Cullen Bryant stand on a large jutting rock which looks just like an enlarged version of the one in the lower left of Hetzel’s painting. It is thought that Durand used Katterskill Gorge as the setting for the foreground in Kindred Spirits and borrowed loosely from the area of the falls and the mountains behind the falls. As you can see in my study of Katterskill Gorge, there are no elevations behind the top of Katterskill Falls. That is a relatively flat area back to North & South Lake whose drainage creates these falls. Another observation which can be drawn from Hetzel’s painting is that the gorge has widened considerably since 1869. Laurel House, a guest hotel, was built at the top and to the left of the Falls. (This site was established around 1827. At its height it housed 250 guests.) Drawings of the hotel, gardens and lanes show that much of the tree cover had been removed to enhance the view of the two levels which constitute the falls. If Hetzel’s foreground is near accurate in 1869 what one finds, now, is a dramatic change. Today the gorge is a jumble of trees and rock. It looks like the result of years of intense flooded flow which uprooted and replanted both trees and large slabs of rock. Katterskill Falls’ lower half is now congested from a collapse of both tree and stone. A geologic interpretation might point to the rapid removal of ground cover adjacent to the falls during the occupancy of the Laurel House guest hotel.

A visit to the site of Sanford Gifford’s painting Artist Sketching at Mt. Desert, ME 1864-65 brings me to my final observations. I was taken by the emptiness of the coastal lowlands depicted in the center of Gifford’s view. Currently the areas between us, from the lower slopes of the mountain to the mouth of the small harbor, are fully wooded (mostly hardwoods). Within these woods is a nature center with streams and accompanying trails. It reminds me of the subtext of much literature I have read about development patterns in the NE during the 19th century. Think of the Atlantic coastline and the major river systems as conveyor belts. Rapid utilization of resources took place along these belts/superhighways. This is especially significant for the Hudson/Lake Champlain system and the Connecticut River system. It also explains the problem Vermont confronted with its very narrow geographic profile flanked by the Hudson conveyor belt on one side and the Connecticut conveyor belt on the other. It was simply too easy to get at the resources and too easy to transport them out. More remote areas such as the Adirondacks or the Shawangunk Mountains (south of the Catskills) were difficult to develop because of their terrain (even for profitable tourism). With a name like Mt. Desert it would seem to be inaccessible. But it is now called Acadia National Park and the mountain top is called Cadillac. You can drive to the top of the mountain. If the timber on the lower accessible levels of Mt. Desert has been redeployed to aid human progress, this would be the norm for the 19th century given the site’s easy accessibility for transport by sea. Gifford’s Mansfield Mountain, VT 1859 would be a site much like those in the Shawangunk Mountains of NY --- too hard to develop on a grand scale. However, I suspect the grand view we are given has been cleared out a bit to reward any hiking party who wants to gaze across the entire western half of VT. I’m not pointing automatically to natural forces anymore when I see a painting that contains tree stumps, broken pines or pine trunks from which the foliage has been stripped.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed